By Charis Morgan

In the face of the global coronavirus pandemic–which had infected 1,657,441 and killed 98,034 Americans by May 25th when George Floyd was killed by a Minneapolis police officer–people across more than 140 U.S. cities mourned the loss of yet another unarmed Black man and took to the streets to protest ongoing police brutality in the United States. Within five days of Floyd’s death, the world watched as Minneapolis and other U.S. cities were set ablaze, as businesses were looted, as protestors and journalists were brutalized by police in riot gear, as the National Guard took hold in 21 American states, and as demands for justice burned through communities united in grief. These images of outrage and violence came as a bitter intermission to the images of illness and unemployment that have plagued the U.S. since early March.

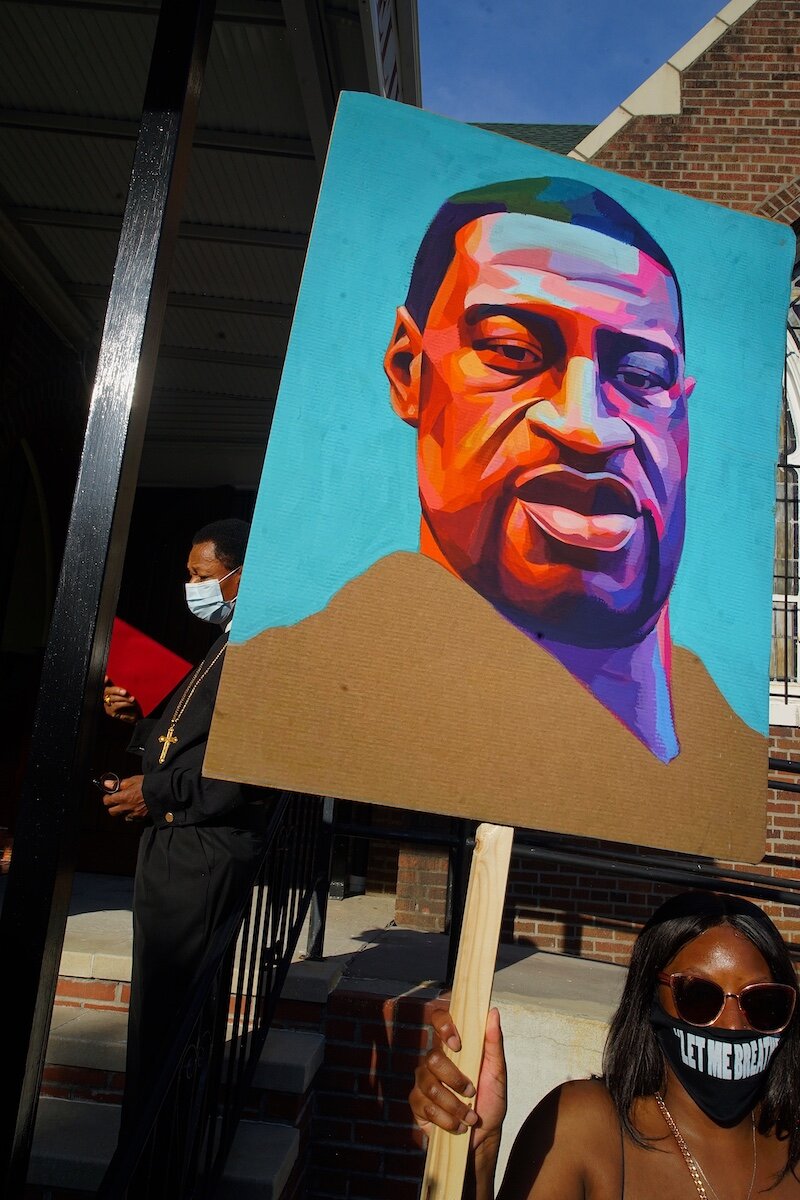

However, Brooklyn based photographer and Vice President of Harlem’s Kamoinge Collective, Russell Frederick, set out instead to capture the nuances of a community that was pushed to the front of the global stage overnight. On May 31st, Frederick departed New York for Minneapolis where he worked for over a week and a half alongside his Kamoinge colleague, Laylah Amatullah Barrayn, and Minneapolis-based comrad in visual activism, Nina Robinson. The photographers worked together covering different aspects of Minneapolis’ reaction to Floyd’s death “whether it was capturing some healing, photographing protests, talking to people and taking portraits, being an amplifier for people, and trying to find some of the untold stories which weren’t making headlines,” said Frederick. By then, the larger protests that had characterized the previous five days had been quelled by the National Guard leaving more intimate rallies and vigils in their wake.

Frederick took note of the Minnesotans who remained engaged over this week-long period after the initial protests, calling on their city to take substantive action toward racial equality. They, and Americans across the country, demanded yet again that their government protect its citizens from injustice and hold police accountable for their unjust actions. “I was really energized to see so many white people genuinely going to the streets to take action for a cause that was a step toward equality and justice for Black people,” said the photographer who recalled two men taking a knee in front of a mural of George Floyd–an homage to NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s 2016 silent protest during the national anthem. Additionally “the Muslim community,” Frederick emphasized, “was also out there in solidarity with us. This was largely the Somali community [of Minnesota] out there on the front lines in support and talking about their own experiences with police brutality. I was a stranger from Brooklyn trying to connect with the community. One day I was visiting the Gordon Parks High School and then I went to a Muslim elementary school and I told them I was a photographer from New York that needed to use the restroom. There were nothing but ladies in there and they allowed me in to use the bathroom. Here I am, a strange Black man with cameras and a mask on my face, and they welcomed me.”

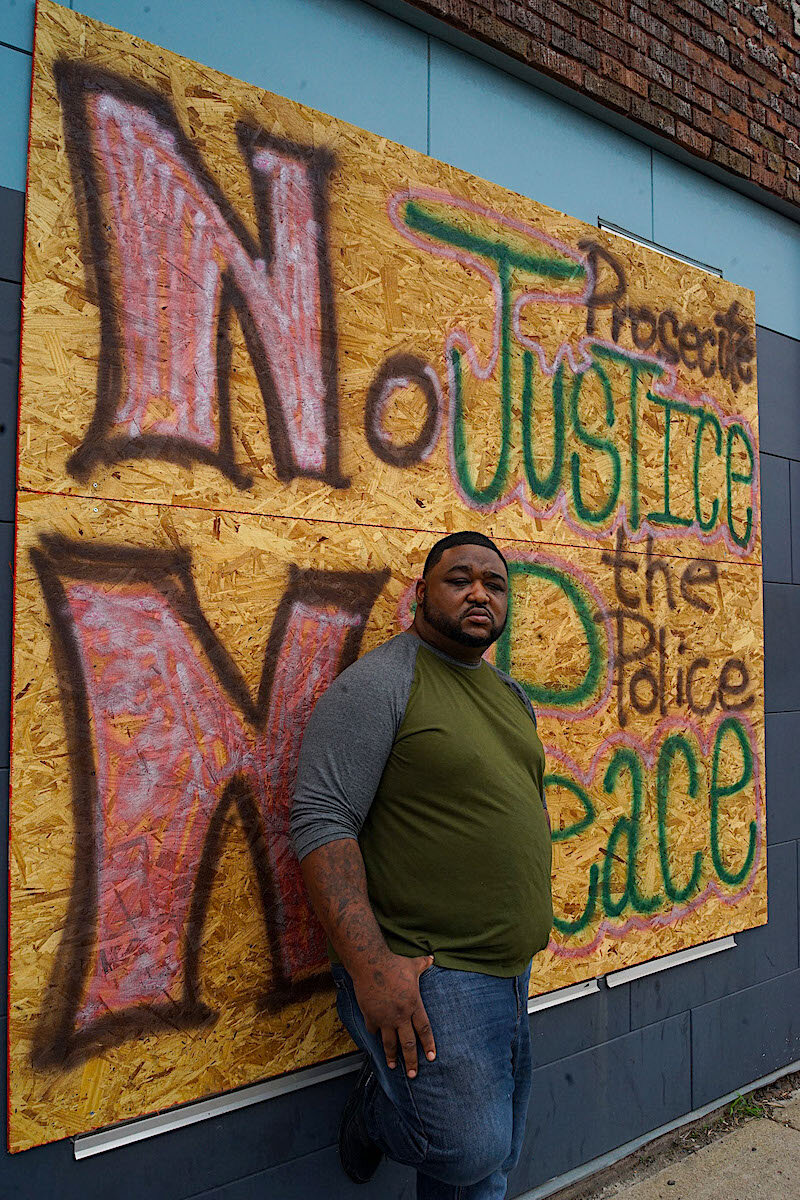

It was also around this time that reports emerged which attributed at least some of the destruction–arson and looting–in Minneapolis to white supremacist groups who were targeting Black establishments. Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey tweeted on May 30th, “we are now confronting white supremacists, members of organized crime, out of state instigators, and possibly even foreign actors to destroy and destabilize our city and our region.” Mayor Frey asked that protestors and community members abide by the 8 PM curfew “so [law enforcement] can focus on saving our city from those who would destroy it.” For many members of the Minneapolis community, particularly Black business owners and Black community leaders, the mayor’s plea was less than compelling. How can a community that cannot rely on local law enforcement to protect the lives of Black Minnesotans entrust the MPD and National Guard with the protection of their neighborhoods, their businesses, or their schools? Frederick spoke with and photographed a number of men from the community who organized–with the help of the local NAACP president, Leslie Redmond–to protect Black-owned businesses within the community on their own. “Dance studios, restaurants, and barber shops had been set on fire and they were not going to allow this to continue” said Frederick of the men who stood on guard in Minneapolis over multiple days and nights. “The men were on rooftops, on the ground, they set up checkpoints to monitor all traffic in and out of the community of North Minneapolis at night. They were on alert and guard for anybody who may be “suspicious,” he recounted.

Frederick pointed out that these scenes undoubtedly echoed the imagery surrounding the Black Panther Party which had set out to defend Black communities against unjust policing some 50 years ago. A burning Minneapolis reminded the nation of the Black businesses scorched during the Tulsa Race Massacre in 1921 and ignited conversation about the historical patterns of destruction in Black communities by white supremacists. Many of the images coming out of Minneapolis and other cities across the United States after Floyd’s death remind us that while the structures which uphold racism have morphed throughout American history, the disenfranchisement of Black communities has remained constant. “These people with evil intentions, trying to hurt us, moved in and attacked our community. With that, all they did was set a spark for us to work together on how we need to protect each other because we can’t depend on the police. The police aren’t there for us, they aren’t our allies,” explained Frederick. Instead, those who spoke with the photographer said they wanted the community to have the agency to protect and care for itself with the support of the local government.

This current moment–which is largely characterized by social unrest, economic downturn, widespread illness, and sadly, death–has underscored the value of the collective in a generally individualistic American society. The wellbeing of the American people is now in the hands of local communities and small governments and the effects of this shift have been far reaching. The issues of agency, representation, and social responsibility have notably taken hold of the world of art and photography. Even before George Floyd’s death, artists have been asking art institutions to replace vague statements of solidarity with racially conscious actions. Floyd’s murder, and the flood of media coverage that followed, imbued these demands with urgency. Who would photograph this historic moment and how they would photograph it? Many argue that the best way to document the Black experience is to give agency back to Black documentarians, Black photographers, Black journalists and scholars. Within days of Floyd’s death, a list of hundreds of Black photographers who were covering the protests was circulating on Instagram, its creators urging assigning photo editors to prioritize Black voices. It now permanently lives as a database on Diversify Photo’s website. A number of photography print sales emerged in support of racial justice organizations. Black Archivist, a project by photographer Paul Octavious which collects and redistributes camera donations to Black artists, encouraged support in light of the increased attention to the initiative.

It is crucial, according to Frederick, that American visual culture highlights more than Black pain, Black grief, and Black oppression. “This is why Kamoinge, a Kikuyu word from Kenya that means ‘a group of people working together’ was formed in Harlem, NY in 1963. The collective committed itself to creating photographs that showed the African diaspora in a dignified manner.” Visual activism, he asserts, means capturing the full humanity of Black Americans. “From the first photograph, photography has been weaponized against us. When I think about the first images of us, it was as slaves. The world saw images of us as subservient, as uneducated, downtrodden, and broken. The second wave of images was us being lynched and hanging from trees,” he said. “The Black community in [Minneapolis] is really trying to advance itself while living in this predominantly white state–trying to preserve their culture, live peacefully, and create business and opportunities for prosperity. To see their loss and to try to capture their resilience, humanity, dignity, their advocacy, and their unity to fight and defeat this beast called racism and white supremacy,” has been an honor and his duty said Frederick.

Russell Frederick is a photographer and visual activist based in Brooklyn, NY. Frederick’s work seeks to redefine the visual narratives of black and brown people with photographs showing their humanity. He is the Vice President of the Kamoinge Collective of Harlem, NY. His twenty-year documentation of Bedford Stuyvesant, Brooklyn has been exhibited widely across the U.S, Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia.