PCPP stands in solidarity with the Black community and the activists working toward change. Beyond displaying signs of solidarity, it is crucial that we take action against the systems and policies that uphold injustice. Below is a list of general resources, places to donate, petitions to sign, and information for photographers.

Read moreJohn Loengard (1934-2020)

Photographer John Loengard died this week. Loengard began his career in photography during his senior year at Harvard College when he was given his first assignment for LIFE magazine. He spent the next three decades working as the picture editor of LIFE Special Reports all while exploring “the ordinary and the unexpected” in his own photography. Loengard’s lifelong dedication to exemplary photography shines through in his work and will leave a lasting mark on the field. Read more about John Loengard’s legacy here.

“It’s always the case that the shutter opens briefly and lets the camera marry reality to form. That union gives the picture structure and defines the moment that lives on.” - John Loengard

A Conversation with Shawn Walker

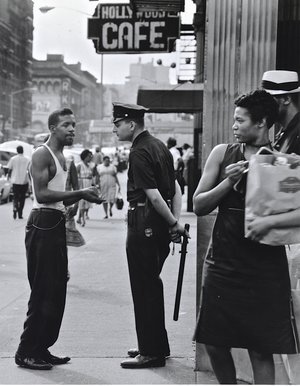

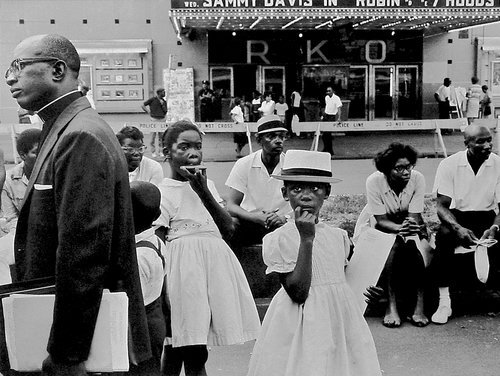

In February of 2020, PCPP facilitated an acquisition of artist and cultural anthropologist Shawn Walker’s archive of photographs, videos, and related ephemera by the Library of Congress. The year prior in 2019, PCPP sat down with Walker to discuss his practice over the years from his earliest days experimenting in the darkroom to his membership of the Harlem-based photography collective, the Kamoinge Workshop, and beyond.

Nicole Kaack: Can we talk about the beginnings of Kamoinge and how you became, to some extent, a repository for a lot of the material that is part of the Kamoinge collection today?

Shawn Walker: Kamoinge is a Harlem-based group, so initially, pretty much all the members lived in this community. We took on the name Kamoinge at Al Fennar’s house when he lived on 112th Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenue. We held a lot of our meetings at James Ray Francis’ house on 120th Street between Lenox and Seventh Avenue. Herman Howard and Herb Robinson lived on East 125th Street. So, I just remember us always being a part of the community.

I came out of high school. I was educated in the North and not a lot of people knew about Northern education; information on race and culture was severely lacking. I went to high school for photography and had an uncle in my family who was a photographer. So when I was going to high school and thinking of my career, my family asked, “What are you going to do?” You have to remember, during this time, some of the political leaders thought all we could do was manual labor, so there were only cooking programs and auto mechanics training. There were two high schools you could go to which were trade schools essentially. So I picked photography. It was around 1950 when my mother began talking to her brothers about the reality of me going into photography in high school and whether it was feasible for a young black man to do this. Usually high school was where you established a more conventional trade. However, they ultimately agreed and that’s when I began my formal training. When Roy [DeCarava] came, he made it clear that what we were pursuing was an art form. So, I think that’s the approach I took to photography and the community. I wasn’t trying to document what was going on in the community; I was trying to create fine art work which discussed issues and elevated the subject matter.

Al Fennar was in the air force so he had spent time in Japan and Herb Randall had spent time in Europe. So we were composed of people with degrees and travel experience; a sundry of different experiences and educations. I started looking at Russian films, Swedish films, Spanish films, French films, Italian films, and we began studying the masters; particularly Dutch painters like Rembrandt and chiaroscuro. We trained as artists, we didn’t train as journalists, so I think that was what Kamoinge meant for me in regards to my education. Most of the Kamoinge members had been involved with federally-funded programs before so that was how we got involved with academics while working with programs that had community control. Back in the late ‘60s and ‘70s, there were a lot of people trying to get black folks in the community to have more control over the schools. There was a lot of federal money, so we wound up photographing demonstrations and rallies, and eventually all ended up in the schools. My first teaching opportunity was at C.W. Post of Long Island University. Ray Francis, Lou Draper, and Herb Randall worked at Intermediate School 201 here in the Harlem community, as well as with Youth in Action in Brooklyn.

Following my first job, I went from stock clerk in the supermarket to working on a weekly newspaper. I used Ray Francis’ name as a reference and took my portfolio in. After I introduced myself to the woman in charge, she told me that I could run the [department]. I thought, Are you kidding? I didn’t even know if I could do the job, let alone run the program. As I mentioned earlier, all of my training comes from Kamoinge. The woman and I went back and forth negotiating, as there was about a $25 to $50 dollar difference in salary for me working as a photographer versus running the photographic department at the newspaper. This was around 1963 or ‘64. After our discussion, the woman said “Ok Shawn, I’m not going to force you into something that you don’t think you can do,” so I took the less pay and went upstairs. That’s when I realized I could run the department. She knew it, I just didn’t know it yet.

Kaack: You mentioned that your uncle was a photographer. Is that, to some extent, how you were introduced to the medium even before high school?

Walker: Yes it was. I remember he once played a trick on me. He was developing some film at my mother’s house and showed me his 2-1/4 camera. The film of 2-1/4 cameras has paper backing. So he showed me this paper backing at first, then turned off the lights and hid the paper from me. After he developed the film, he took this plastic roll with images out of the tank and I thought to myself: “Oh man, he’s turned paper into plastic.” I was very intrigued and wanted to know how I could do this. It wasn’t until much later that I found out that the film actually had a paper backing. Nonetheless, this experience is what set the ground for me thinking about photography as magic. From a young age, I understood that there was a magical part of photography in that you were capturing time. You are taking something out of its place in time, frozen in this moment that you can now put it in your pocket. You can carry it away and open it up ten years from now and that moment still exists in this photograph. That’s the magical part about it. That’s where the historical and anthropological implications come through.

Karen Gaines: How did you go about choosing your themes for your collections? You have series such as Harlem and Halloween, but some of your contemporary work is not just one theme. For instance, when you created the self-portraits, it wasn’t called Self-Portraits, it was titled The Invisible Man. Can you talk about this process and how you went about creating these themes?

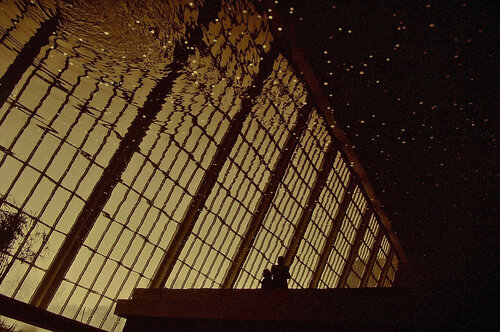

Invisible Man Series © Shawn W. Walker

Walker: During the ‘70s, around the time when they began having demonstrations about the war occurring in Vietnam, I began working on a range of series–including one about nuclear bombs. I did research on neutron bombs and began trying to understand how we as Americans could design devices that destroyed people, yet left behind infrastructure. I read about the atomic bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima and how some people had been vaporized, leaving behind only a physical shadow. As a result, my research on the neutron and atomic bombs is what prompted me to start organizing my work and motivated me to create the Shadows series.

I have to give credit to the work of the Soho artists I was viewing during this time. They were splashing all kinds of commentary and posters–a lot of material, onto the walls, which got me thinking about appropriation. I would always photograph things that I thought I could add some part of myself into and claim as my own. After 20 to 25 years of photographing, it was through Shadows that I really began thinking about the technique and magic of photography, and the fact that we were working in a two dimensional form. I was introduced to the late M.C. Escher who created complex prints in which he printed over his canvas repeatedly to create a three-dimensional work. Now, I understood how you could view this two-dimensional object and look at it from above, below, from the sides, and every other angle. That struck a chord in me and motivated me to recreate this feeling within my own two-dimensional art. I then began photographing windows, especially those which contained mannequins.

I was also inspired by science-fiction movies, and the generic endings in which after destruction, the survivors would wind up going to a store to get clothing and other supplies, and there would always be mannequins and small creatures like cockroaches which were left behind. So when photographing these windows, I was trying to create optical illusions. I wanted people to look at these works and question: “Where is he? What time period is this? What’s behind the glass? What’s behind me?” Through this approach I was able to add six or seven layers visually that the viewer could be seeing at one time. I went from talking about the black community, black problems, black issues, black injustice, to talking about something more universal: about bombs and destruction, and the way we gear up to kill people. Now, I began trying to talk about larger issues, about art, about science, and about magic. The most recent work involving these ideas had to do with my images of windows, which I called the Bebop Series; Bebop referring to Jazz. Everyone in the Kamoinge group were jazz heads. Bebop is a term that was given to a particularly black type of music in the beginning of jazz, involving figures such as Dizzy Gillepsie, Charlie Parker, and Thelonious Monk. All of these guys had taken American music and made it their own. So I began trying to add this element into my own work. I was trying to do something a bit more creative than what I was initially doing. I had done cultural anthropological studies, so now I was trying to talk about my cultural experience in a contemporary way.

Kaack: Can you delve deeper into your feelings about social responsibility and how it shifted over time?

Walker: I began talking about social issues such as the atomic and nuclear bombs because these are issues that are broader than just my community. After a while, if you don’t learn that racism is a product of another illness, you’ll begin to attract it in that area of your life. I create videos now. I like costuming and rituals so I film parades. You have people coming from all over the world bringing their rituals, their culture, with them. One of the ways you take pride in yourself and dismiss society is by being part of a parade. I’ve shot the Korean Parade, the Chinese New Year Parade, and the Afro-American Day Parade, among others. So this is what I do to continue talking about culture, about race and class, and preserving history. Now I can create work that satisfies my soul. I’ve been doing this for a long time and needed to show that I’m growing. That there is more to my art than talking about the illnesses of society in a very direct, obvious way.

Gaines: Do you get frustrated that it seems people only ever want to talk about your early work? The work from the sixties, the work of early Harlem, the ‘stereotype’ of what Harlem used to look like or is that just the culture? Is that what is missing in museums and what people are looking to fill gaps in?

Walker: I think to some extent, yes. I remember early on doing assignments that were normally geared for white photographers. White photographers wouldn’t go up to Harlem, so instead they would get a black guy to do it. I think it’s because there was a lack of white photographers experiencing certain periods of time in Harlem due to fear, that we don’t see more of this work in museums.

The people I photographed weren’t middle class. They were below working class here and I made that very clear. I was fortunate enough to have two working parents and just one brother. The guys I hung out with only had one working parent and some of them had six or seven siblings. But the stereotype of the working class was why black people were very conscientious about the way they looked. I remember when I was 26 years old, living in my mother’s house, she wouldn’t let me go out on Sunday without a suit. This was because she knew what the neighbors would say. But that was her own complex about the neighbors. I was trying to photograph the gritty part of Harlem life. The series on drug addiction was about guys I was hanging out with, I didn’t choose that specific theme. Though I might have photographed it, it wasn’t anything that I celebrated. The reason why those photographs became public was because Adger Cowans saw them and said that Essence Magazine was looking to do a story on drugs. It was not something that I promoted. Like I said, these were my buddies, so I tried to photograph the life that I knew existed for all of them.

Both of my parents worked. My dad fortunately got a union job on the Jersey Pacific railroads. Do you know how many black men had union jobs back in the forties? So we were pretty well off. But I took to photographing the people I was associated with: my friends. However, I never understood why I didn’t quite fit in. I tried to fit in, but I wasn’t conscientious of how my class and status affected me. The guys used to say, “You don’t fit in because you ain’t one of us. You eat all the time. You got all the stuff. You got clothes, you got the skates. We don’t have that. We can only talk and dream about it.”

Nikisha Roberts: What is your prediction of the future of photography? What do you think it will be like to have a career in photography in the coming years?

Walker: You need to do this for yourself. If you do it for yourself, then there's no disappointment about what happens to it. Whether it gets discovered, whether it doesn’t, you make it the best you can. You preserve it. And then history deals with it at some point. You have to understand that I began doing this for me. I took care of my work and continued collecting because I wanted this to last. It has given me a purpose in life. It has allowed me to reflect and think, “Okay, you’re a local guy who came off the block and look what you have become.” I’ve been an educator for 40 years, I’ve been recognized as an artist, and now my work will be in a major institution. You have to remember my life expectancy back then was 55. I made it past drugs, I got around jail. I got through alcohol. So today I consider myself very lucky. I’m okay.

Gaines: So what do you think of Harlem today?

Walker: Harlem is not Harlem anymore. During the time that I was growing up, Harlem was a community. When my mom and I sent my brother to the store, the neighborhood would watch out for us. When I decided I wanted to smoke at around 12 years old, we had to go four or five blocks away. Even then strangers would catch you and say "Where you belong boy? I'm going to take you to your mother for smoking those cigarettes.” Now Harlem is a tourist destination. The community no longer exists. There are community-minded people here, there are people still battling for that, but everyday is a struggle against the evolving real estate industry. We will sell anything out. We do not care about history. It's about what we can build, how high we can build it, and how much money we can make off of it. That's what's happening to Harlem. My haven is here. This is why all of this is important for me. This is where I live. I'm a part of this community, but this is also where I live, in this apartment here. This is my studio. This is where I function, this is where I can do the things that preserve me when dealing with the folks outside.

Image credit: Shawn Walker, Karen Gaines, Nikisha Roberts, and Nicole Kaack in Walker's home studio. Photo taken by Lizette Terry.

Roberts: As you continue to produce work related to abstract photography, what are some topics and themes you hope to tackle in the future?

Walker: I don't do stills as much as I used to. I do a lot more video as I'm getting older. I've grown tired of lugging equipment. Even my lightweight gear becomes problematic. I have a ton of video to go through so that’s what I’m focusing on at this moment in time. The work that I create depends on where I'm at, where I'm going, and what I'm exposed to. I have a neighbor who lives next door, her name is Rashidah Ismaili and her place is called the Salon d’Afrique. She does parties: Kwanzaa celebrations and dinner parties and she’s a serious African cook. It amazes me to see the people that attend her parties. There are dancers, drummers, and a wide variety of artists. So I go there, geared up, ready to film. I go with a monopod and a bunch of film. So if I don't do anything else for the rest of my days, as long as she has parties and she's in the next building, I will go and photograph her events because they’re historic. I never have thought much about what I'm going to be doing next. There's enough stuff that I need to be doing right now like going through my files and naming all of the musicians and personalities that I’ve documented. My future is going to be about preserving this information for younger generations.